Caveat: I have yet to knit my first pair of period stockings, although I've knitted modern socks. These are notes I've made while researching the subject.

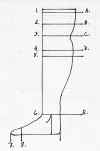

Chart for making your own custom knitting pattern:

Gauge, or Stitches per inch:

Some stockings are described as 'coarse', which may correspond to the

5 to 6 stitches per inch reported from a shipwreck in New France or the

8 stitches per inch of the Gunnister man's stockings (Pulliam, p. 31).

The gauge increases through 9 st./in. (Gehret), 12 st./in. (Gehret, Burnston)

all the way up to much finer gauges in the range of 22 st./in. for very

fine stockings, but that certainly takes us beyond the realm of 'common'

stockings. The very finest gauge stockings were almost certainly knitted

by machine (knitted flat, with increases and decreases along the edges

for shaping, then sewn together). 18th century knitting machines could

knit in gauges from 10 to 30 stitches per inch. Coarser

gauges (as low as 2.5 st./in.) were used for items such as mittens and

hats.

You will want to knit a swatch to figure out your final gauge. Knit a circular swatch rather than a flat swatch if you are knitting in the round; most people purl at a slightly different gauge, which will throw off your calculations. It may be advisable to knit a pair of modern socks with the needles and yarn you intend to use for your period stockings to make sure your measurements will give you a good fit.

Yarn:

Worsted wool, cotton, linen, and silk were all used. Common stockings were usually knitted out of worsted yarn, i.e., yarn

spun from combed rather than carded wool. Wool spun this way has a harder

finish than carded wool, because the fibers are all lined up in the direction

of the spinning, so they have less loft (i.e., aren't as fluffy), whereas

yarn that is carded has the fibers lined up perpendicular to the direction

of spin (very fluffy). To understand the difference, think about the finish

on a man's wool suit (combed), as compared with wool for knitting sweaters

(carded).

I ultimately want to knit my stockings using yarn that I have spun, but I may order some yarn for my first pair of period stockings. Knitters on the Historic Knitting list recommend various sport weight or lace weight yarns (two ply, not singles). It will probably be easier to knit your first pair of stockings in wool rather than linen, silk or cotton, since wool has more give and is easier to knit. A pair of stockings should take about 8 oz. of wool yarn, depending on gauge and the size of the stockings, but ordering extra yarn is always a good idea.

Colors:

Black, white, and blue were common colors, with blue being a particularly

common color among the working classes. Other colors include brown (dark

to tan), gray, and "sheep's black" (actually a brownish black),

"cloth colored" (natural tannish-white yarn), and speckled or

'clouded' (made by plying two colors of yarn together). Bright colors

such as red, yellow and purple were not unknown, but may have been more

common for *silk stockings rather than worsted wool. There is some debate

in reenacting circles about the color green, but Farrell has several references

to green silk stockings in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Through 1730, stocking colors usually complemented the color of the suit or dress; after that date, white stockings were generally worn with formal dress. At the very end of the century (1790s) very fancy striped stockings become fashionable; with the exception of a possible example worn by a sailor in a mid-18th c. illustration, striped stockings don't seem to have been common before the end of the 18th century. Ribbed stockings, however, were worn. The ribs were vertical, measuring 3/4" wide (Farrell, p. 31).

There is no documentation behind the rumor that red, green, or yellow stockings denote anything unsavory about the wearer. In fact, there are both green and red stockings with provenance tying them to women of good reputation.

Stockings were patched, had the feet replaced, redyed, etc. to extend their lives (Dunleavy p. 88)

Needles:

Double-pointed metal needles were used in the 18th century for knitting

stockings; wooden needles may have been used for knitting some larger-gauge

items like caps. If you intend to knit at reenacting events, buy needles

that aren't coated with a noticeably non-period color, like pink or mint

green. If your local yarn shop doesn't carry or can't order small-gauge

steel needles (size 3 down to 0000), you can order them from Lacis,

Halcyon

Yarn, The Mannings, or

various other online knitting suppliers.

You may want to order two pairs of needles in each size, so that you can knit both stockings at once. A few winters ago, I knitted one stocking down to the ankle, then lost my notes on how many rows / increases / decreases I'd made, so rather than waste the yarn, I ripped out all the work and will have to start over.

I'm still trying to figure out the issue of 'stretched gauge'. Some knitters recommend removing 10% from your calculations to account for stretch; others recommend measuring your swatch while it's moderately stretched.

Tops:

Various designs for the tops of 18th century stockings include:

Three rows purl, two rows knit, two rows purl, one row knit, one row purl,

then plain knitting (Irish stockings, Dunleavy p. 88)

Several rows of garter stich (six, in Burnston p. 100-101 and Pulliam,

p. 30-31)

The welt at the top of the stocking helps keep the top of the stocking from rolling and serves to keep the stocking from slipping down below the garter.

Early 19th century stockings shown in Rural Pennsylvania Clothing have k2, p2 ribbing at the top instead of rows of garter stitch.

Back 'Seam':

The back 'seam' on knitted stockings is probably an artifact from cut-and-sewn

hose, which, of course, had their seam down the back. Cut-and-sewn hose

(which don't fit as closely as knitted stockings) were still worn by some

in the lower classes into the early 19th century, at which point machine-knitted

stockings were cheap enough that they displaced them. In knitted stockings,

the 'seam' helps the knitter to mark the beginning of each round, and

is a convenient place to put increases and decreases.

Styles:

purled every row (Dunleavy, p. 88)

purled every other row (Burnston, p. 101)

six-stitch seam (?) (Pulliam, p. 31)

Gussets and Clocks:

Clocks, when present, were worked on both sides of the ankle, not just

one side.

On common stockings, the heel-flap-and-gusset style shown here seems to be fairly common. This gives you a short gusset to the ankle; the longer gussets seen in some 18th c. artwork may be a feature of machine-knitted stockings.

Purl-stitch clocks (Gunnister stockings, Pulliam p. 31) and embroidered

clocks were used; a common method was called "plating", in which

the design was added using an additional color knitted into the fabric

of the stocking. This can be imitated by embroidering the stockings with

a duplicate stitch following the shape of the knit stitches.. A rose-and-crown

motif was one of the more common designs. When the gore is a different

color from the rest of the stocking, the embroidered clocks usually match

the color of the gore. Some surviving silk stockings also have clocks

embroidered in gold or silver thread.

On a pair of wedding stockings, a knitted gusset extending above ankle,

with details such as a zigzag and diamond pattern on either side of the

clock in purl stitches, and a rose and tree clock design above it in purl

stitches (Burnston, pp. 100-101).

Heels:

The most common treatment seems to have been the 'common heel,' in which

the heel flap is folded in half and bound using a three-needle bindoff.

However, if you do a modern heel, few people will notice unless you take

your socks off.

Some of the stockings from Rural Pennsylvania Clothing have a k1, sl 1 ribbed heel. These stockings are all early 19th century, and I'm not sure if this kind of ribbing is a feature of early 19th century knitting, or whether it's an earlier feature of Pennsylvania Dutch knitting. Two of the stockings shown in the book have the heel turned as mentioned above, while others have a more modern heel turning.

Toes:

Equal decreases on either side of foot (Burnston, p. 101); also called

a 'mitten tip' toe. Also see this

page on Socks 101.

Instead of grafting using Kitchener stitch (which seems to be 19th c.),

use a three-needle castoff to bind the toe.

Links to other useful knitting sites:

The Carnamoyle

Stockings, by Kass McGann

Hand Knit Hose

by Deborah Pulliam

Knitting Period Stockings,

by Drea Leed

Making 18th

Century Fitted Stocking by Rebecca Manthey

The Sock Calculator

(for modern stockings; you plug in your knit gauge and measurements)

Museum

of London pic of stocking, infant's knitted vest, and mitten

Knitting Tips and

Information for Re-enactors by Phyllis and Paul Dickinson

Basic knitting advice:

Knitting tips and tricks

at Maggie's Rags

References:

A

History of Hand Knitting by Richard Rutt

Dress

in Ireland by Mairead Dunleavy

Fitting

and Proper by Sharon Ann Burnston

Gunnister Man's Knitted Posessions, by Pulliam, Deborah. Piecework,

September/October 2002. Loveland, CO: Interweave Press.

Rural Pennsylvania Clothing by Ellen J. Gehret

Socks

& Stockings by Jeremy Farrell

Books on Knitting:

Folk

Socks by Nancy Bush-- not a book on period knitting, but can help

with reconstructing period knitting techniques; see comments on this book

in the Historic

Knitting List archives

Knitting

in the Old Way: Designs and Techniques from Ethnic Sweaters by Priscilla

A. Gibson-Roberts (Caveat: sweaters as we know them in the 21st century

were not worn in the 18th century, but knitted vests or waistcoats were

worn as undershirts under other clothing for additional warmth. I'm including

this book because I like it and it helps clarify some older knitting techniques)

Also visit the Historic Knitting List on Yahoo Groups

Free online video clips of basic knitting stitches can be found at http://stitchguide.com/

A few words on crochet and tatting: Both crochet and tatting are 19th century techniques. There are a few books around that talk about crochet and tatting dating back to the 15th century or earlier, but so far, those who have looked for or looked at the textiles in question either find that they're nonexistent or are mislabled needle lace or knotting (which are not the same as tatting), or nalbinding (which can look a little like crochet but is really not the same thing). An essay on the subject, written by someone much more knowledgeable on the subject than I am, can be found in the files of the Historic Knitting List. If you can find actual existing objects (not just a second- or third-hand reference in an arts and crafts book) made with tatting or crochet dating earlier than the 19th century, I'm sure the folks there would be happy to see the evidence.